Tearing down the last vestiges of social trust… as a path back to social trust.

<<Woodcutter and Priest sit in a ruined city gate>>

Woodcutter: I don’t understand. I just don’t understand. I’ve never heard such a strange story. I don’t understand it at all.

<<Commoner enters>>

Woodcutter: I just don’t understand.

Commoner: What’s wrong? What don’t you understand?

Woodcutter: I’ve never heard such a strange story.

Commoner: Why don’t you tell me about it? We happen to have a wise priest in our midsts.

Priest: No, not even the renowned, wise priest from Kiyomizu Temple has heard a story as strange as this.

Commoner: So you know something about this strange story?

Priest: This man and I have just seen it and heard it ourselves.

Commoner: Where?

Priest: In the courthouse garden.

Commoner: The courthouse?

Priest: A man was murdered.

Traveler: Just one? So what? On top of this gate, you’ll find at least five or six unclaimed bodies.

Priest: You’re right. War, earthquake, winds, fire, famine, the plague…. Year after year, it’s been nothing but disasters. And bandits descend upon us every night. I’ve seen so many men getting killed like insects, but even I have never heard a story as horrible as this.

Woodcutter: Yes. So horrible.

Priest: This time I may finally lose my faith in the human soul. It’s worse than bandits, the plague, famine, fire, or war.

These are the intriguing opening lines of Rashomon. What is the bizarre story, more horrible than war, earthquake, murderous bandits, etc.? It turns out that it’s just a story about a rape and a murder. Isn’t that a bit of a let down? It’s not obvious what makes that all-too common evil more horrible than the former, but I’ll come back to that shortly.

Here’s some of the opening lines of another story, this one a true story, from Adrienne LaFrance’s article in the Atlantic:

One place to begin is with Edgar Maddison Welch, a deeply religious father of two, who until Sunday, December 4, 2016, had lived an unremarkable life in the small town of Salisbury, North Carolina. That morning, Welch grabbed his cellphone, a box of shotgun shells, and three loaded guns — a 9-mm AR-15 rifle, a six-shot .38‑caliber Colt revolver, and a shotgun — and hopped into his Toyota Prius. He drove 360 miles to a well-to-do neighborhood in Northwest Washington, D.C.; parked his car; put the revolver in a holster at his hip; held the AR-15 rifle across his chest; and walked through the front door of a pizzeria called Comet Ping Pong.

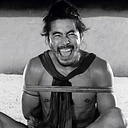

Shortly after I heard about Lyrebird and Deepfake technology I changed my avatar on various social media accounts to Toshirô Mifune in Rashomon. My own take on Rashomon, commonly dissected by both film students and philosophy students, is that the horror they speak of which exceeds that of war, earthquakes, murderous bandits, etc. is of course not the rape and murder per se; rather, it is the disregard for truth and the idea that getting at the truth — even from those we would expect to have the most vested interest in preserving it — might be impossible.

My half-baked idea, until now expressed only in an avatar change, was that developments in technology like Lyrebird and Deepfakes have the potential to throw humanity into a period of deep skepticism and destroy social trust. People are already deeply skeptical of “the media” and the opposing political party. What happens when technology like Lyrebird becomes better and easily accessible to the public? How will we know which message comes from the president or our local mayor?

For governments, hashing and signatures might provide a way to avoid the full extent of the problems that would arise here. But that’s not a simple solution. Signatures would have to be checked by media outlets prior to releasing statements or footage. But that still leaves the problem of social distrust in media itself. The biggest problem may not be how governments verify and trust information (though this might become a bigger problem for less developed nations) — but how the citizens verify and trust information.

What happens when scammers and hackers target this technology towards private individuals? Imagine receiving a fake phone call from your wife or your daughter traveling abroad, or seeing a fake photo of your husband in an affair?

While I still think this technology provides a looming challenge that we aren’t yet ready to meet, the Atlantic article gave rise to another half-baked idea of how it may also solve a problem which we already find ourselves entangled in. This is the problem of being caught in a sort of river hole of trust.

The ‘river hole of trust’ (there’s probably a better phrase to describe this, but that’s all the effort I’m putting into it for a half-baked idea) is the state in which our levels of social incredulity and social credulity are such that people can easily drown by their inability to properly assess which information is trustworthy, but still have a high degree of faith that they’ve found at least a handful of trustworthy sources.

Edgar Maddison Welch is the perfect example of the type of person I have in mind. Welch exhibited incredulity towards mainstream media, but credulity towards certain new media outlets and social media circles. This is what leads to my half-baked idea that the trust-destroying forces which may come with Deepfake technology may be the catalyst to break free from a river hole or trust.

Put differently, one way of breaking a river hole of trust by developing wisdom. But this presents its own major challenge with a sort of bootstrapping problem. Another way to break a river hole of trust is more quick and dirty. If people like Welch had a reason to be more skeptical — if his cone of skepticism expanded to all of what he reads or watches on social media and new media — he would have never found himself walking through the front door of Comet Ping Pong brandishing weapons.

The disruption caused by deepfake technology may serve a useful purpose if it forces us to adopt the same behavior that the virtue of epistemic humility would lead us to. But that’s just a temporary stopgap.