The Seductive Framing of Exposure

In their paper Technologically scaffolded atypical cognition, Alfano et al. note that, according to a paper by Neil Levy, “even if one approaches [fake news and other sources of falsehoods] with caution, one is liable to be taken in.”

But it’s worth pointing out that the reasons for this are not due to any characteristic unique to fake news or falsehoods (at least not as Alfano et al. indicate in their explanation of Levy’s point). The reasons for this are the mere familiarity effect and the seductive framing of exposure. These are phenomena of human psychology that apply to any type of information.

That’s worth pointing out because if it were the case that we were especially susceptible to fake news or falsehoods we might think this as a motivation for some kind of fact-checking tsar. But it might also have broader negative implications for the reliability of our cognitive faculties.

Still, these phenomena might have other negative implications. If we have a high information intake (are spending a lot of time on social media or news media) and all of it is coming from a very narrow perspective, these may exacerbate radicalization.

Seeking a balanced perspective (does this entail a more accurate perspective?) doesn’t necessarily mean reading Breitbart and Huffington Post. That might or might not help one achieve a more balanced perspective, but there is an obvious practical difficulty involved here. People are reluctant to spend much time listening to or reading content that they already believe they know is false. They will also treat such content with a high degree of suspicion. Even if, say, an Andrew Klavan fan is not sure how the Pod Save America crew is wrong about some specific topic, it’s still not going to carry any weight with with the Klavan fan.

Thus, if one is deeply embedded in far right-wing or left-wing content, simply supplementing that with far left-wing or right-wing content is a step that many people may not have the time or motivation to do. But there’s an easier and, maybe, better solution. It can also be as simple as realizing that conservative media and progressive media exist along a spectrum. The bent of National Review is not the same bent of The Daily Wire and neither one have the same bent as The Dispatch. All of these fall on the conservative side of things, but at different points of the spectrum. It’s more practical (and, given certain assumptions, better) to broaden your intake of perspectives in this narrower sense. If you’re fully convinced that conservativism is correct and you have limited time, add one or two sources of your intake from within that spectrum.

—

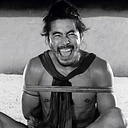

P.S. The bias of the authors, or simply that it comes across so clearly in the paper, is pretty surprising. Ben Shapiro, martial arts, and fitness are among the things presumed by the authors to be “problematic content.”